Behind the Scenes

This was the first challenge I did from Hack The Box. I started it because there was a newcomer at the club, and wanted to do some Reversing together. Me, as a newbie myself, picked something easy, the one with the most solves.

I started by strings as in every challenge, regardless of the category.

We can see something interesting by piping the strings to grep strings behindhtescenes | grep -n HTB -B 2 -A 2,

19-[]A\A]A^A_

20-./challenge <password>

21:> HTB

22-:*3$"

23-GCC: (Ubuntu 9.3.0-17ubuntu1~20.04) 9.3.0

From Line 20 and 21, I assumed that the program takes as input a password.

I run strace with a dummy password as argument:

strace ./behindthescenes babisgkantantougkas

Interesting… We can see clearly a SIGILL situation going around here.

Enough with the assumptions, let’s jump into Ghidra and do some disassembling.

After the initial analysis is done, we navigate to the defined strings of the program and search for the interesting ones we found via strings.

Under the defined string ./challenge <password> there is the following sequence of characters in plain sight.

Itz_0nLy_UD2

Spoiler alert, this is probably the flag! Anyways, it says something about UD2. Let’s dive more into that.

“Generates an invalid opcode. This instruction is provided for software testing to explicitly generate an invalid opcode. The opcode for this instruction is reserved for this purpose. Other than raising the invalid opcode exception, this instruction is the same as the NOP instruction.”

A useful shortcut to search in Ghidra is Ctrl + Shift + e (see Ghidra). We search for UD2 enabling Instruction Mnemonics and jump to the first hit. We disassemble the code below UD2. There are 2 more hits of UD2 now. By reading the disassembled code, we can see that a comparison with the weird found string is being made. This is the first invocation of strncmp.

iVar1 = strncmp(*(char **)(*(long *)(unaff_RBP + -0xb 0) + 8),"Itz",3);

/* And so on, for the rest of the comparisons */That’s about it.

PS: The newcomer never returned…

Simple Encryptor

Writing the reverse script in python posed the most significant challenge for this one.

Before trying to reverse it with Python (guess what 🤡), it is important to know this relevant piece of information:

“In C, the rand function is part of the standard library, and its behavior is implementation-dependent. It typically uses a linear congruential generator (LCG) algorithm.

On the other hand, Python uses the Mersenne Twister algorithm.”

Anyways, let’s reverse it using C.

/* ... */

df = fopen("flag.enc","wb");

fwrite(&seed,1,4,df);

fwrite(string,1,pos,df);We can see that in flag.enc the first four bytes (integer) is the seed. So after reading the seed, we can easily generate the rest of the numbers and reverse the operations.

The solution in C is something like that:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

/* Myrto */

/* Rev - Simple Encryptor */

int main() {

int seed;

char *content;

size_t size;

FILE *f;

int rand_0;

int rand_1;

f = fopen("flag", "rb");

if (f == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Could not open file for reading.\n");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

fseek(f, 0, SEEK_END);

size = ftell(f);

rewind(f);

content = malloc(size);

if (content == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Could not allocate memory for file content.\n");

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

fread(content, sizeof(char), size, f);

memcpy(&seed, content, sizeof(seed));

printf("Seed: %d\n", seed);

srand(seed);

for (size_t i = 4; i < size; i++) {

rand_0 = rand();

rand_1 = rand() & 7;

content[i] = ((unsigned char)content[i] >> (rand_1)) |

((content[i]) << (8 - rand_1));

content[i] = rand_0 ^ content[i];

}

for (size_t i = 4; i < size; i++)

printf("%c", content[i]);

fclose(f);

free(content);

return 0;

}Bypass

Oh, it’s .exe time. That was my initial reaction with this challenge.

Let’s begin by… guess what… file and strings.

Bypass.exe: PE32 executable (console) Intel 80386 Mono/.Net assembly, for MS Windows

Oh no, .NET 🤮.

...

.NET Framework 4.5.2

...

I’m going to be brief with this challenge. There was a tool that made my life easier, which was __.

I opened the executable with dnSpy for 32-bit and started debugging it.

public static void 0()

{

bool flag = global::0.1();

bool flag2 = flag;

if (flag2)

{

global::0.2();

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine(5.0);

global::0.0();

}

}I changed the value of flag2 from false to true so that the branch is being taken and see what will happen. After that, we get into the global::0.2() function where the user is

prompted to enter a secret key.

The key is ThisIsAReallyReallySecureKeyButYouCanReadItFromSourceSoItSucks if you look more carefully the Locals section. We type the key and get the flag.

Exatlon

First, I ran the file command.

exatlon_v1: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (GNU/Linux), statically linked, no section header

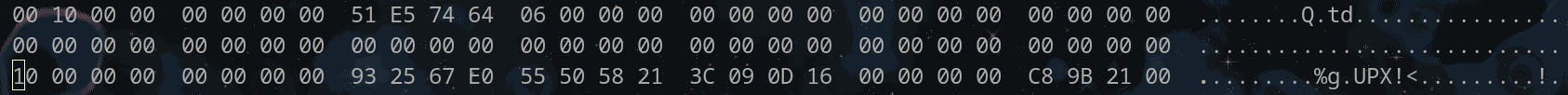

If we open the file in hexedit, we can see that there is a UPX string. That means that the executable is likely packed. This leads to the conclusion that the original executable is compressed.

To decompress the executable, we run:

upx -d exatlon_v1 -o exatlon_unpacked

where -d is the flag for decompression and -o for redirecting the output to a file.

Then, we open the unpacked executable to Ghidra and wait the analysis to finish. We can see beautiful C++ code unfolding in front of our eyes!

There are two things that raise suspicions. Those are the exatlon(parameter) function that is being called, and a comparison with some weird values after the exatlon invocation, that looks like this:

std::operator==(parameter, "1152 1344 1056 1968 1728 816 1648 784 1584 816 1728 1520 1840 1664 784 1632 1856 1520 1728 816 1632 1856 1520 784 1760 1840 1824 816 1584 1856 784 1776 1760 528 528 2000 "

);

Let’s unwrap exatlon function. It’s important to note that I changed the name of the function parameter and local variables for clarification purposes.

There is a loop that iterates over the string, does some binary operations and re-assigns it to the parameter passed. Each iteration, the destructor for temp is called. So, it holds the value of the current character shift by 4 bits which then is concatenated with parameter.

/* Left-shifts current character by 4 bits */

std::__cxx11::to_string(value,(int)curent_character << 4);

std::operator+(temp,(char *)value);

/* Reassigns value calculated to parameter */

std::__cxx11::basic_string<char,std::char_traits<char>,std::allocator<char>>::operator+=

((basic_string<char,std::char_traits<char>,std::allocator<char>> *)parameter,temp);

/* I skipped some code (destructors, assignments, advancing the iterator) */To reverse this operation (shift is easy :D), I wrote this simple script in python.

# Myrto

# Rev - Exatlon

encrypted_char_list = [1152, 1344, 1056, 1968, 1728, 816, 1648, 784, 1584, 816, 1728, 1520, 1840, 1664, 784, 1632, 1856, 1520, 1728, 816, 1632, 1856, 1520, 784, 1760, 1840, 1824, 816, 1584, 1856, 784, 1776, 1760, 528, 528, 2000]

decrypted_str = ''.join([chr(char >> 4) for char in encrypted_char_list])

print(decrypted_str)That was it! After unpacking it, it was a piece of cake!

Golfer - Part 1

“This is a story of a reverse challenge, but you should know upfront, this is a steganography challenge.” Narrator

This was a challenge that helped me familiarize with Ida, but because I was not fond of the rich lady in the logo, I tried to solve it on Radare2 (r2) first.

I write more about my r2 experience in the Radare2 section.

Well, I have to say, that in the end, I opened Ida as it was suggested from the challenge hints. I was hating it at first, but now I have an OK relationship with it.

Enough talking, let’s begin the challenge. I have to say that I was quite lost with this challenge. I was looking at the code trying to patch everything but the solution was right in front of my eye.

If you hexdump it:

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 61 34 66 54 55 48 7d 79 52 7b 6c |.ELF.a4fTUH}yR{l|

00000010 02 00 03 00 01 00 00 00 4c 00 00 08 2c 00 00 00 |........L...,...|

00000020 67 5f 33 30 42 72 ef be 34 00 20 00 01 00 00 00 |g_30Br..4. .....|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 08 38 01 00 00 |............8...|

00000040 38 01 00 00 05 00 00 00 00 10 00 00 e9 d6 00 00 |8...............|

00000050 00 fe c3 fe c2 b9 0a 00 00 08 e8 d0 00 00 00 b9 |................|

00000060 08 00 00 08 e8 c6 00 00 00 b9 24 00 00 08 e8 bc |..........$.....|

00000070 00 00 00 b9 0e 00 00 08 e8 b2 00 00 00 b9 0c 00 |................|

00000080 00 08 e8 a8 00 00 00 b9 23 00 00 08 e8 9e 00 00 |........#.......|

00000090 00 b9 09 00 00 08 e8 94 00 00 00 b9 21 00 00 08 |............!...|

000000a0 e8 8a 00 00 00 b9 06 00 00 08 e8 80 00 00 00 b9 |................|

000000b0 0d 00 00 08 e8 76 00 00 00 b9 22 00 00 08 e8 6c |.....v...."....l|

000000c0 00 00 00 b9 21 00 00 08 e8 62 00 00 00 b9 05 00 |....!....b......|

000000d0 00 08 e8 58 00 00 00 b9 21 00 00 08 e8 4e 00 00 |...X....!....N..|

000000e0 00 b9 20 00 00 08 e8 44 00 00 00 b9 23 00 00 08 |.. ....D....#...|

000000f0 e8 3a 00 00 00 b9 0f 00 00 08 e8 30 00 00 00 b9 |.:.........0....|

00000100 07 00 00 08 e8 26 00 00 00 b9 22 00 00 08 e8 1c |.....&....".....|

00000110 00 00 00 b9 25 00 00 08 e8 12 00 00 00 b9 0b 00 |....%...........|

00000120 00 08 e8 08 00 00 00 30 c0 fe c0 b3 2a 90 90 55 |.......0....*..U|

00000130 89 e5 b0 04 90 90 c9 c3 |........|

00000138

We can see some weird characters after the ELF header. They kind of look similar to what a flag would contain: HTB, underscore…

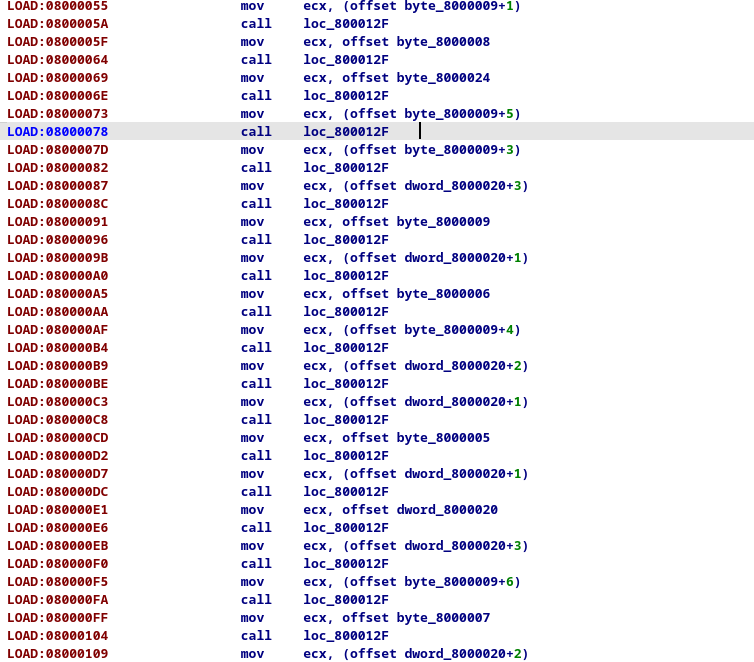

The main program consisted of a simple loop and above it there were those mov-call pairs. I played around with the offsets (right click on the value and select offset option with the pointer to data icon), and see that I could simple extract the characters and construct the flag.

For example:

mov ecx, offset unk_800000A

# ---> H You can see the value by hovering the unk_xxxxxxx. I’m not sure if there was a faster way, but it was quite easy like that!

Congratulations, you are a 🏌️ now!

Cyberpsychosis

A friend recommended me this challenge. I really liked it but again, I spent most of the time exploring some theory stuff.

diamorphine.ko: ELF 64-bit LSB relocatable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), BuildID[sha1]=e6a635e5bd8219ae93d2bc26574fff42dc4e1105, with debug_info, not stripped

Some useful links:

- GitHub - m0nad/Diamorphine: LKM rootkit for Linux Kernels 2.6.x/3.x/4.x/5.x/6.x (x86/x86_64 and ARM64)

- How did I approach making linux LKM rootkit, “reveng_rtkit” ? | reveng007’s Blog

So, what is an LKM?

In computing, a loadable kernel module (LKM) is an object file that contains code to extend the running kernel, or so-called base kernel, of an operating system.

So, first I opened the diamorphine.ko file with Ghidra, and then with Ida for some reason. Both can do the job just fine. Anyways, let’s go to init_module or diamorphine_init (entry point).

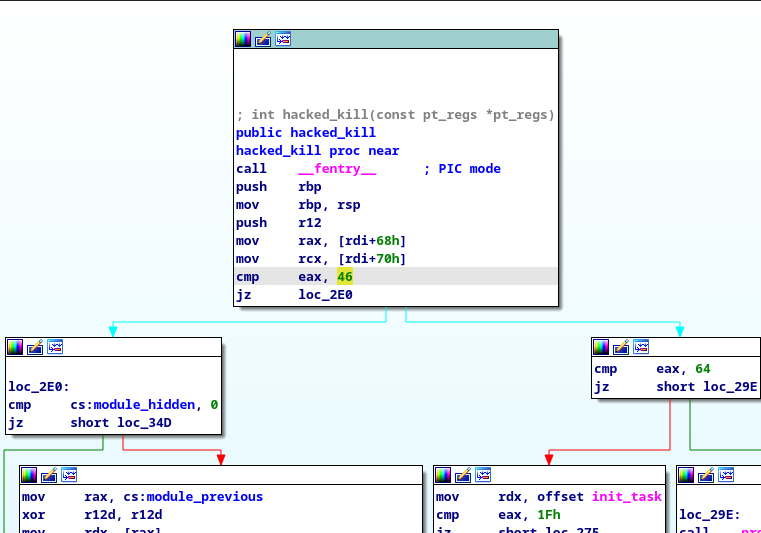

Following m0nad’s repository, we can see that in order to make the module visible we have to:

kill -63 0But in our case, after observing the disassembled code, we can see that we need to send another signal to kill (disarm) the rootkit.

So, after connecting to the instance we resume by sending :

kill -46 0And then to become root:

kill -64 0Then, we can just remove the module:

rmmod diamorphineTo find the location of the flag, I just did some tree-grep thingie (I don’t like find), but let’s also put the find command that I won’t remember it after one day.

find . -maxdepth 10 -type f -name 'flag.txt'Good challenge!

SEPC

This is my first medium challenge from Hack-The-Box platform. I will try to dive into as much as possible. I went to RANDOM.org, assigned some numbers to the available medium challenges and this was the challenge that was selected.

First steps

First we extract the files from the initramfs.cpio file.

cpio -idmv < initramfs.cpioThe important files are:

checker.kochecker

We also can observe the following init script.

# -- init --

#!/bin/sh

insmod checker.ko

mount -t proc none /proc

mount -t sysfs none /sys

mknod /dev/checker c 137 0

chmod 0666 /dev/checker

exec /checkerThe init file first loads the kernel module checker.ko.

We can see that with mknod /dev/checker c 137 0, a new character device is created, with major number 137 and minor number 0.

With exec /checker, the current process in the shell is replaced with /checker.

We can try and reverse both the kernel module and the executable.

/* `main` starting point of the module */

void module_start(void) {

int ret_0;

ulong ret_1;

/* Registers a range of device numbers (major number, number of

* consecutive devices, the name of device or driver)

* */

ret_0 = register_chrdev_region(dev,1,"checker");

if (ret_0 < 0)

_printk(&DAT_0010036d);

else {

/* On success, create a class `checker`,

* (string name of the class)

* */

DAT_00100cc8 = class_create("checker");

if (DAT_00100cc8 < 0xfffffffffffff001)

{

/* Initialize cdev,

* (structure to initialize, file operations (fops))

* */

cdev_init(&DAT_00100c60,&PTR___this_module_001006a0);

ret_0 = cdev_add(&DAT_00100c60,dev,1);

if (ret_0 != 0) {

_printk(&DAT_001003c8,"module_start",ret_0);

}

/* creates a character device and registers it with sfys

* (class, parent, dev_t, data to be added for callbacks,

* string for the device name)

* */

ret_1 = device_create(DAT_00100cc8,0,dev,0,"checker");

if (ret_1 < 0xfffffffffffff001) {

__x86_return_thunk();

return;

}

_printk(&DAT_00100386);

}

else {

_printk(&DAT_001003a0);

}

}

__x86_return_thunk();

return;

}Important functions:

Useful Information / Understanding

I wanted to understand more and kind of refresh my knowledge on Linux devices. These are some nice readings.

- 3.4. Char Device Registration

- IoT Series (IV): Debugging with GDB & GHIDRA + Zero-day - ArtResilia

- Try debugging with IDA or ghidra (I think with ghidra there is a higher chance)

Continuing …

I made a script to debug the checker file just in case by modifying the given run.sh script.

#!/bin/sh

qemu-system-x86_64 \

-kernel bzImage \

-initrd initramfs.cpio.gz \

--append "console=ttyS0 noaslr" \

-nographic \

-s -SThis did not help…

To attach to your gdb session just:

target remote :1234I examined the checker.ko and found the magic comparison! If I had IDA pro, it would be a lot easier to examine the pseudo code, but I gotta look at the assembly code instead for now… No, I’m just an idiot, there is Pseudocode view available.

This is kind of obvious, but it has helped me to search for cmp operands when I know that a comparison is being made. This gets out of hand when the program is huge.

Another hint was searching for _copy_from_user.

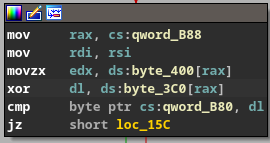

mov rax, cs:qword_B88

mov rdi, rsi

movzx edx, ds:byte_400[rax]

xor dl, ds:byte_3C0[rax]

cmp byte ptr cs:qword_B80, dl

jz short loc_15Cmovzxdst, source (Move with zero extend)- dl

Following the values at the data section, if we xor the sequences, we get the flag. Something that was probably my mistake was that I couldn’t get the final } from the flag.

Rauth

rauth: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=fc374b8206147fac9067599050989191b39eefcf, with debug_info, not stripped

On first observation, we can see that it’s a PIE executable. We will jump into this later.

Calls

Ok, looking at the code we see some encryption going on:

- salsa20…new (alias: salsa20_new)

- salsa20..apply_keystream (alias: salsa20_apply)

Salsa20

Initial state of Salsa20:

| “expa” | Key | Key | Key |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key | ”nd 3” | Nonce | Nonce |

| Pos. | Pos. | ”2-by” | Key |

| Key | Key | Key | ”te k” |

We have to find the key, nonce and the encrypted text in order to be able to get the plaintext.

Solving …

First, we try to find the Salsa20 block somewhere in the code. It should be visible after the call to salsa20_new.

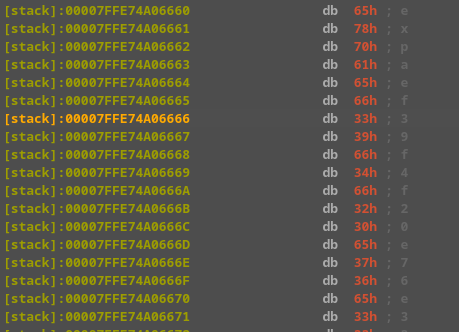

Looking at the stack (breakpoint after salsa20_new) we can see the block:

expaef39f4f20e76e33bnd 3d4c270a3 2-by d25f4db338e81b10te k

Key: ef39f4f20e76e33bd25f4db338e81b10 Nonce: d4c270a3

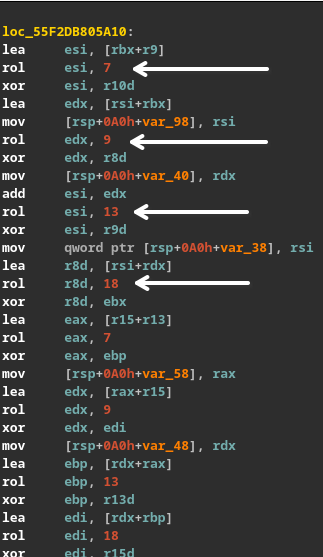

Then we look for the encrypted text. Let’s explore the area around salsa20_apply. I was very confused because I was expecting the encrypted value to be around there. Maybe, I was thinking something wrong! Looking around again at the values loaded by cs (code segment), I can see the following:

.text:000055C15A406611 movaps xmm0, cs:xmmword_55C15A439CC0

.text:000055C15A406618 movups xmmword ptr [rax], xmm0

.text:000055C15A40661B movaps xmm0, cs:xmmword_55C15A439CD0

.text:000055C15A406622 movups xmmword ptr [rax+16], xmm0

.text:000055C15A406626 mov [rsp+168h], rax

.text:000055C15A40662E movdqa xmm0, cs:xmmword_55C15A439CE0

- cs:xmmword_55C15A439CC0 →

0F331CBA656F5D958D5A829A3B15F0505h - cs:xmmword_55C15A439CD0 →

0F91BAD626FB63EE372EC9DC9312A4324h

Password found! Just input it to the prompt now and the flag is yours.

Other stuff I found interesting (not necessary for the solution)

- Salsa rounds:

b ^= (a + d) <<< 7;

c ^= (b + a) <<< 9;

d ^= (c + b) <<< 13;

a ^= (d + c) <<< 18;

- XMM registers

- The

csprefix indicates that the address is relative to the code segment. - The movaps moves a 128-bit value aligned on a 16-byte boundary (movups for unaligned).

- c - Why are global variables in x86-64 accessed relative to the instruction pointer? - Stack Overflow

- assembly - CS: override on access to global variables in IDA output, like mov eax, cs:x? - Stack Overflow

- OWORD = 16-byte data type